North Shore Plant Club

North Shore Plant Club

- Shop For Plants

- Search Plants

- Resources for Gardeners

- Color Wheel of Plants

- Interactive Landscapes

- Photos of Planters & Hanging Baskets

- February Photos from Our Community

- Botanic Gardens: Chicago & Beyond

- Local Nurseries

- Upcoming Plant Events

- Plant Club Articles & Answers

- Gardening in the News

- Chicagoland Garden Calendar

- Explaining Plant Container Sizes

- Thrillers, Fillers & Spillers

- Join Free!

- Mundelein

Feb 7, 2026 12:13 AM

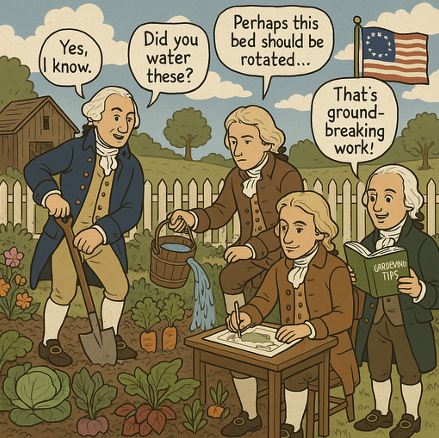

The Founding Fathers in the Garden

When we think of the Founding Fathers, we picture powdered wigs, quill pens, and fiery debates about independence. But what if we told you that these same revolutionaries were also passionate about something far less dramatic—gardening?

Yes, before they were drafting constitutions and declaring independence, they were digging in the dirt, pruning peach trees, and arguing over compost ratios. Welcome to the leafy, loamy world of the Founding Fathers’ horticultural hobbies.

George Washington: The General of the Garden

Before he was the first President of the United States, George Washington was a passionate gardener and agricultural innovator. At his Mount Vernon estate, Washington oversaw sprawling gardens and farmland with the precision of a military campaign. He believed agriculture was the backbone of a strong republic, famously declaring it “the most noble employment of man.”

Washington’s gardening style was both practical and experimental. He rotated crops to preserve soil health, composted organic waste, and tested new plant varieties. His gardens included vegetables like peas, beans, and cabbage, alongside fruit orchards and ornamental plants. He even kept detailed records of planting schedules and harvest yields—think of him as the original spreadsheet farmer.

But Washington’s love of gardening wasn’t just about food. It reflected his vision for America: self-sufficient, sustainable, and rooted in the land. He saw farming as a civic virtue, a way to cultivate not just crops, but character.

Thomas Jefferson: The Veggie Visionary

While Thomas Jefferson is best known for penning the Declaration of Independence, his true passion may have been farming. At Monticello, his Virginia estate, Jefferson cultivated over 300 varieties of vegetables and herbs, transforming his garden into a living laboratory of botanical experimentation.

Jefferson approached gardening with the same intellectual curiosity he applied to politics. He imported seeds from Europe and Asia, tested planting techniques, and meticulously recorded his results. His garden journals—filled with notes on germination rates, harvest yields, and weather patterns—read like scientific treatises. He once wrote, “The greatest service which can be rendered any country is to add a useful plant to its culture.”

Monticello’s terraced vegetable garden was not just functional—it was a statement. Jefferson believed that agriculture was the foundation of democracy, and that independent farmers were its most virtuous citizens. His landscape sketches often included both aesthetic and practical elements, blending Enlightenment ideals with earthy pragmatism.

James Madison: The Soil Scholar

Often hailed as the “Father of the Constitution,” James Madison was also a quiet champion of agriculture and soil science. At his Virginia estate, Montpelier, Madison didn’t just grow crops—he cultivated ideas about sustainability, stewardship, and the delicate balance between land and liberty.

Madison believed that the health of a republic depended on the health of its soil. He studied erosion, nutrient depletion, and crop rotation with the zeal of a naturalist, and he advocated for responsible land management long before it was fashionable. His writings reveal a deep concern for the long-term viability of American agriculture, warning that careless farming could undermine the very foundations of democracy.

While other Founding Fathers were busy sketching garden layouts or experimenting with exotic vegetables, Madison was reading agricultural treatises and giving lectures on land conservation. He saw farming not just as a livelihood, but as a civic duty—an extension of the principles he helped enshrine in the Constitution.

John Adams: The Cranky Cultivator

Then there’s John Adams, the curmudgeonly patriot with a soft spot for sunflowers. Adams was less flashy than Jefferson and less methodical than Washington, but he loved his garden with the passion of a man who’d just survived a Continental Congress. Adams believed that gardening was not just a pastime—it was a moral and civic exercise. He saw the act of cultivating land as a way to stay grounded, humble, and connected to the rhythms of nature.

His garden was practical and patriotic, filled with staples like corn, beans, and squash—the “Three Sisters” of colonial agriculture. Adams wasn’t flashy about his horticulture, but he was fiercely proud of it. He often wrote to his wife Abigail about the state of his crops, sometimes with more enthusiasm than he reserved for politics. One letter said: “I must study politics and war that my sons may study mathematics and philosophy… and their sons may study painting, poetry, music, architecture, statuary, tapestry, and gardening.” That’s right—gardening was the pinnacle of civilization in Adams’ eyes.

Gardening as Political Philosophy

For the Founding Fathers, gardening wasn’t just a hobby—it was a metaphor. Cultivating a garden required patience, planning, and respect for nature. Sound familiar? It’s basically how they approached building a nation.

Jefferson believed that farmers were the backbone of democracy. Washington saw agriculture as a path to independence. Madison viewed land stewardship as a civic duty. And Adams… well, Adams just wanted to be left alone with his beans.

Their gardens were microcosms of their political ideals. They tilled the soil of liberty, planted the seeds of democracy, and weeded out tyranny—sometimes literally.

Digging the Founding Fathers

Today, you can visit their estates and see the gardens they once tended. Monticello’s vegetable terraces are still thriving. Mount Vernon’s fields are still plowed. And Adams’ farm still grows the same crops he once fussed over.

Their legacy isn’t just in documents and monuments—it’s in the soil. The Founding Fathers were gardeners of democracy, and their love for the land helped shape our nation.

So next time you’re pulling weeds or planting basil, remember: you’re walking in the footsteps of revolutionaries. And if your tomatoes don’t turn out, just blame the British!